I have worked in the fields of justice, public health, education, and writing. Remarkably, all paths have led to the same end: centering stories that bring people together and drive meaningful conversations.

My love of storytelling is born of my family’s immigrant experience.

My father, who has a tenth-grade education, is a born storyteller, his talent honed by sitting, as a child, in a fishing shack in Nova Scotia, listening to lobsterman share yarns around a potbelly stove.

My Sicilian grandfather, who had even less education, ritually told me the tale of his passage to America in 1921, how he left his beloved village and crossed the Atlantic in a liner that almost went down in a storm. My Sicilian grandmother inspired my love of poetry, often reciting Shakespeare and the Psalms. She worked as a seamstress and sewed costumes for my sisters and me so we could put on shows – the enactment of stories. I remember well the embroidered shawl, fan, and full skirt I wore while singing, “I Like to Be in America.” I was ten.

My minimally educated forebears guide my approach to teaching, which I see as more than the assembly of paragraphs or the application of grammatical rules. It begins with the conviction that each of us has a voice, though we may lack the confidence to set it free. To that end, my students read, write, discuss, and “make mudpies,” as I describe the process of grade-free generative writing.

At the end of each semester, whether they are in “Ethical Missteps in Public Health” or “Composing the Self” – a history and memoir class, respectively – students write a personal essay on some aspect of how identity intersects with their experience of health, education, or life as a first-generation American. They stand up and read the work to the class. Without fail and with permission to write about anything, students consistently lean into writing about their deepest vulnerabilities.

Surviving school shootings, being tasked with lighting a deceased father’s funeral pyre, childhood sexual abuse, enduring police frisking because of race, fear of speaking Spanish in public, terror of ICE, estrangement from parents, life in a trailer as a migrant farm family, the “unbelongingness” arising living between old and new cultures, publicly embracing LGBTQ2+ identity, sitting through class while one’s homeland is being bombed — these are a few of the many stories I have been privileged to hear.

Why do they choose to tell such stories?

Our culture lacks public rituals for collective grieving, and it comes at a cost. At the end of each semester, I stock up on Kleenex and jokingly tell my students that crying is a teachable moment. That’s true, but I also want them to know that it’s okay if they cry. Attentive listening is the kind of witness-bearing that builds community. It is “love thy neighbor” in action, and it changes lives.

I will never forget the young woman who clearly struggled with anorexia. She stood to read an essay about being attacked and said, “I can’t read if they look at me. Can you ask them to turn around?” She read her essay through tears and tremors with me by her side. When I saw her the next semester, she looked happier and brighter. She said, “You saved my life.” I disagreed but she continued, “I ate on the days I had your class.” She had gained fifteen pounds and made friends with her classmates… having set her voice free.

I have no special power to elicit change, but I do possess the willingness to welcome whatever shows up at the classroom door. In those last weeks of the semester, my students lead and I follow.

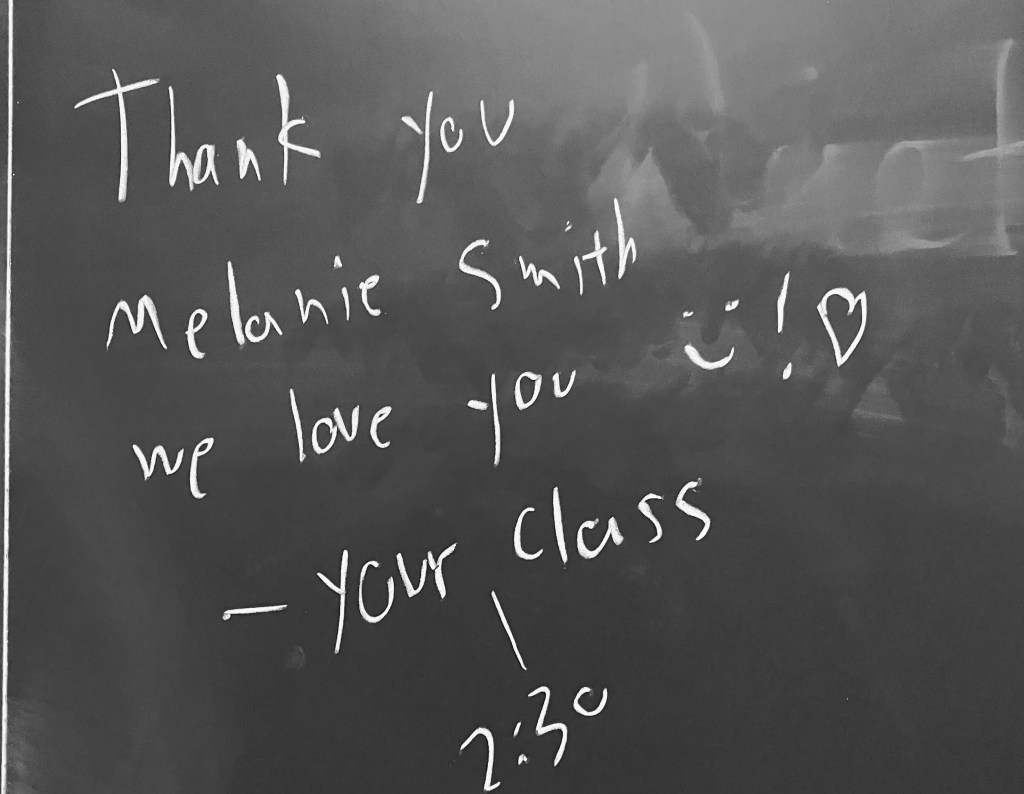

On a particularly dark day in 2025, I received the following message from a former student, who perhaps best expresses how I approach teaching:

Hello Professor Smith,

You may not remember me, but this is Valeria. I was one of your students, both in my freshman year the semester COVID hit and my junior year for your writing 153 class. Though it has been several years now since you have taught me, I just wished to express gratitude for the things I learned in your class, and for the very real human experience you brought within the classroom. Few professors at BU had the impact on me that you did, and I wanted to thank you for believing in my writing. I am in law school now, and though life still comes with hardships and complexities, I often find myself living life with the intentionality I learned of in your memoir writing class. Every morning is sun shining on my skin, every night a quiet resilient breath beneath the stars. Professors play such a large part in what a student decides (or fails) to pursue. You held compassion towards your students where others held condescension. For that, I wanted to thank you.

Though I am currently taking a small detour from writing, I hope to publish something like a memoir one day, and even my mere hope I can do so is because you believed in me.

Thank you, Prof. Smith!

Thank you, Valeria!

Thank you, to all my students, for teaching me how to listen.

Leave a comment