What did I know, what did I know

of love’s austere and lonely offices?

— Robert Hayden, “Those Winter Sundays”

My great grandmother’s backyard in Argyle Sound

Nova Scotia’s Evangeline Trail begins in the Southwest port of Yarmouth and follows the shoreline northward 181 miles to Grand Pre. Six miles out from the trailhead, on a bluff overlooking the ocean, sits a village of tiny cottages as uniform and clean as beach pebbles except for two places where the row is broken, each by a bare white steeple. A barren expanse of long stiff grass lies between the village and the tiny cluster of worn fishing shanties that dot the shore. Beyond the shacks is the sea, steel-gray in winter and blue in summer, with waves that sparkle like diamond-dust. Clouds of gulls shriek and circle the shabby but brightly colored lobster boats as they putter toward shore, and on clear days the rattling of boat engines carries across the water. On stormy days sheets of wind blow up off the ocean and over the bluff, whipping at the trees and grass and muting human voices. In winter the land sleeps under a blanket of white, the whisper of snowfall like a long last breath.

The only other sound on days both calm and tempestuous is that of the rhythmic silver tide as it ascends then tumbles back over sand and shell and rock, turning up the stuff of the sea itself.

It is for some a child’s bedtime lullaby and for others, a ceaseless dirge for fishermen gone.

#

Much of who I am I owe to a man I never knew, who lived in Nova Scotia and died in 1955, seven years before my birth. No firsthand account of his life remains, no letters or journals, nothing save the wedding license on which he scrawled his name in 1932: Douglas R. Smith, R for Ripley, a melodic name that suited him well. The slim man staring back from a sepia wedding photograph had large clear eyes under an upturned sweep of hair and a shock of bushy eyebrows, and the tiniest hint of mirth in one corner of his mouth. His smooth-skinned, fair-haired teenaged bride bore a more placid smile, though she had the unmistakable pale eyes of the white-haired lady named Cynthia whom I grew up calling “Nannie.” But Nannie’s husband was a thickset ruddy-faced and balding fisherman I called Grampy Vic. By the time I found the sepia photograph, I knew that Douglas had died of pneumonia when my father was a boy. That meant that Grampy Vic was Nannie’s second husband and wasn’t my biological grandfather. As yet unknown were the circumstances under which Nannie and her first husband, having no children of their own, had taken in my father as an infant. Later, when I learned the facts of my father’s adoption, I would gaze at the sepia photograph of the newlywed innocents and regard Douglas in particular as a stranger, unaware of his magnificent role in my father’s life, or by association, in mine. Over Nannie’s kitchen sink was a window with a telescope to search the shoreline for boats chugging toward a protected cove where the fisherman would moor them in winter. I was like a boat in that unruffled cove, shielded by an impregnable stone breakwater that arced like an underwater arm to keep the harsh elements at bay.

That invisible breakwater was Douglas Ripley Smith.

Most family secrets can be uncovered if you are tenacious. Births, marriages, and deaths—all are marked with certificates. Securing such documents inked in rural Nova Scotia, where my father was born in 1937, would turn out to be no small feat. It was do-able if you had decades to wait. But documents don’t tell stories; they merely pin dates. The records were a first step, and even when my father’s adoption file was unsealed—he was 82 years old by then—his full story had yet to be revealed. It came in increments, jogged by my questions and jogged as well by the leather-bound photograph album I would eventually smuggle from Nannie’s attic during one of my last visits before her death. By then I knew the significance of telling her that I had never seen a photograph of my father as a baby. But even that confession was rooted in far earlier questions posed innocently by a little girl with the prescient awareness that she did not know her own father.

“How did you learn to fix things, Dad?” I asked one day as he perched on a stepladder scraping and painting. I was a pigtailed fourth-grader sitting cross-legged on the floor; at thirty-something, he was thick-shouldered and bearded, with only a fringe of fine hair on the sides.

“Fix what things,” he answered without looking at me.

“House stuff,” I said. “Like painting. Who taught you?”

“I learned in school, the same as you.”

I took classes in reading, math, and art, not in fixing things, but I pressed on.

“Why didn’t you become a fisherman like Grampy Vic?”

He snorted.

“How the hell’re you going to fish when you get seasick every time you set foot on a boat?” he asked, as if this were something I should know. “I used to get sick as a dog.”

This was news. I had spent many an afternoon crammed in a station wagon with my younger sisters while my father cruised slowly along coastal places, silently studying the very thing he professed to dislike.

I nonetheless persisted.

“How old were you when you came here?”

“Eighteen.”

At nine or ten, I hadn’t the depth perception to understand what it meant for a teenager to leave his home and immigrate to another country, nor had I a mental picture of my father at that age. In my mind, he had always been stern, taciturn, and preoccupied.

He continued silently to paint, and I continued to watch. At some point I asked him “Why didn’t you stay there?” or “Why did you leave?”—I don’t remember exactly. What I do remember is the answer that ended my questions, delivered as deftly as a nail driven in with one blow.

“I wouldn’t give you ten cents for that place.”

He either didn’t want me to know or he didn’t want to remember. Yet somehow, even as a kid, I perceived the armor. I had seen it the night his beloved hunting dog Sandford was killed by a car. My father came up the street cradling the corpse in a bloodied quilt, tears streaming from his reddened eyes.

“You kids get back,” he ordered, as much to shield three crying kids from his anguish as from the canine carnage.

“Leave Dad alone,” my mother had shushed us as he went out back to dig a grave in the woods. That night would be the only time that, as a child, I saw my father cry.

Sandford was the same name of the childhood village he claimed wasn’t worth ten cents.

His forestalling my litany of questions was the lid of the coffin interring a lifelong shame. Children perceive that shame and wrongly believe it attaches to them. I was no different. Shy and bookish, eventually I became depressed that everything I did—or didn’t do—seemed to elicit the same fury from my father. Leaving bedroom shades unevenly drawn, returning a nearly empty cereal box to the shelf, or squabbling with my sisters: All were occasions for rage. And he came after me, hand raised, more times than I can count, mostly at the behest of my mother. The most prominent feature of family life was my parents’ need for complete control, and I was uncontrollable, not because I wasn’t a good girl—I got A grades and didn’t smoke or drink—but because they were deeply unhappy. When I left for a college a thousand miles away, it wasn’t a celebration. It was elective self-exile, in some circles called “a geographic cure,” and ineffective.

Long intervals separated my visits home. Away from the family, I aimed high, joylessly obtaining one then another degree and competing for prize jobs, while back at home my father was driven to work with an urgency that even injury and illness couldn’t dampen. When he dislocated a foot by jumping off a gigantic excavator, he snapped the foot back into place and kept on working; that evening, my mother had to cut the boot from the swollen foot. When he began to suffer chest pains at the age of 54, he ignored them. I wouldn’t have said, when I received the call that his life was in jeopardy, that we were compelled by a common shame. I knew only that a risky surgery awaited my one and only father. Walking alongside the gurney that wheeled him to the OR, I sent up a silent prayer.

“Please don’t die before I have the chance to know you.”

He had inherited a heart defect, though from whom was a mystery. I was about twelve when I had learned a family secret so dark, I was not to speak of it.

“I’m going to tell you something you’re not supposed to know,” my mother said conspiratorially one day as she folded laundry. “Nannie’s not your real grandmother. Your father is adopted. But you can’t tell anyone.”

My father’s “real mother” was my great Aunt Regina, a woman with icy eyes and stiff curls. Aunt Gina, as we called Nannie’s older sister, had not one shred of maternal instinct. Her unyielding body had the warmth of a lamppost.

“Like a little bull in a china shop,” she crowed when I moved about the tiny house decorated with crystal knick-knacks and plastic upholstered chairs. “Mind the little blunderbuss doesn’t break anything!”

Aunt Gina had a son named Wally, a guy we rarely saw but whom I nonetheless feared because of his loud and palsied speech. I didn’t understand that he was alcoholic and partially deaf. But now, as I thought about the new revelation, I realized how much he resembled my father. Did Wally know they were brothers? No, my mother said; Aunt Gina had run away as a teenager and married Wally’s father, but she left him because he beat her. Wally had been raised as the seventh child in the brood of my great-grandmother, or “Big Nannie,” as we called her.

So who else knew? I wanted to know, and how did they know? As a boy, my mother told me, my father had overheard the adults talking in the kitchen below a heat grate in his bedroom floor. He hadn’t let on that he knew, but as a young man he had gotten confirmation from another aunt. What’s more, everyone in the family knew. The only person from whom the secret was explicitly withheld was the bastard child himself.

There it was: the betrayal that birthed his shame.

I mentally filed the “secret” away without wondering about my biological grandfather. The revelation didn’t make much difference to me. Nannie loved my sisters and me, and clearly adored my father. On our annual visits to Nova Scotia, his voice rang with rare delight in her pride. So eager was she to please him that she practically tripped over herself offering up his favorite brown bread, chowder, and pickles. When she wasn’t making jam or hand-kneading bread dough, she was knitting. She passed out handmade hats, mittens, and woolen socks as casually as if they were cookies.

I might never have given the “secret” a second thought had my father not brought it up himself. The day before that open-heart surgery, he fetched me from the airport, stopping on the way home for a cup of coffee. Now in my thirties, I felt the old discomfort of not knowing how to talk to him. I shared the only news I could think of, that my adopted boyfriend had found his birth mother, who was Sicilian, like my mother.

“’Course a kid wants to know where he comes from.” My father gazed out the window, his pale eyes fluid in the bright light. “Take me for example. I’ve often wondered who my real father was, but the guy’s probably dead by now.”

I froze. How had I been so dumb as to broach the subject of adoption?

“I’d like to find out who he was,” he said. “That would really be something.”

I asked an obvious question: Wasn’t the name on his birth certificate?

“I don’t have a birth certificate,” he said bluntly and stuck a toothpick in his mouth.

I envisioned my own birth certificate, a slip of embossed white paper with two frog-like footprints, the time and date of my birth, and my parents’ names. It was the “once upon a time” to my own life, deep history that I could nonetheless touch. How could my father not have one?

“Can’t you just ask Nannie?” I asked.

He frowned, incredulous.

“Your grandmother’s been real good to me, and I don’t want to upset her. I’ll wait until she’s gone.”

It might be a long wait. Most of my paternal forebears had hung on until well into their nineties and one, to 106. My father put loyalty to the woman who raised him above his own burning desire to learn a painful secret he had carried for decades.

This was also news.

The day after his surgery, I visited my heavily sedated father. His eyes were closed and a breathing tube was in his mouth. “He looks asleep, but he can hear you,” said the nurse. I slipped my fingers into his lifeless hand, and almost imperceptibly he squeezed, as if to say, I am still here.

With sudden clarity, I understood the importance of unearthing his birth-story. The gesture that joined our hands like links in a chain told me it would be just as important to me as to him.

I made him a silent promise.

“I am going to find your father.”

But years passed, and—distracted by my own life—I did not find his father.

One day my mother telephoned with surprising news.

“Some guy emailed us claiming to be your father’s younger brother,” she said. “I looked him up—he has a criminal record.”

Then she added, “I want a DNA test.”

The ordinary man—Chuck—in the photograph she sent could very nearly have been my father’s twin. Aunt Gina had put him up for adoption not in Nova Scotia but in Massachusetts, which now made it easier for adoptees to find birth parents. That might account for the news that Chuck knew the identity of their father: one Ernest Ellis, a Sandford local whose name had been whispered in our family for years. Clearly the relationship between Ernest and Regina—if the information was accurate—had lasted long enough to produce two children. Why hadn’t they married? In thinly populated provincial Nova Scotia, out-of-wedlock births would have been impossible not to notice. For now, the question had no answer.

My father wasn’t ready to meet his brother, but the revelation of Chuck’s existence prompted renewed albeit hushed talk about my father’s paternity. My curiosity again piqued, I paid a visit to Nannie, now widowed and living alone.

“Why aren’t there any baby pictures of my father?” I blurted out one day.

Her answer surprised me.

“Why, my dear, he’s got a whole baby book of pictures up in the attic somewhere.”

To my frustration, she resisted fetching it, so the day before my departure, I crawled into the eaves and retrieved it myself. My subterfuge was well rewarded by the thick leather-bound volume that held an abundance of old family photographs, the first of which depicted a round-faced baby of about six months, a bonnet fastened under his chin. A partially concealed arm propped him up as he reached for a jaunty kitten that trotted by.

I dropped to the floor, half blinded by sudden tears.

When Nannie found me crying, she sat cross-legged beside me, genuinely perplexed.

“Why are you crying, dear,” she laughed. “He was a very happy baby.”

I couldn’t have explained it to her if I had tried—my long-held faith that underneath the burly guy who worked “heavy construction,” whose rage was frightful and whose thickset hands proffered “a wallop you won’t forget,” was this.Softness personified. A bundle that, like all babies, invited cuddling. I couldn’t remember a time he had ever cuddled me.

A few years later, visiting Nannie for the last time with my own baby son and aware that her faculties were failing, I would smuggle out that album and be glad I had. When she died, relatives carted away dishes and handmade quilts. The album that likely would have gone from one attic to another held many untold stories, and I studied it.

Among the photographs were early snapshots of Aunt Gina, first as a plump swarthy teenager and later, slimmer, with sleek dark hair tucked under a hat. There was no obvious evidence of the “wild girl” my mother had described and to whom she attributed heritable maleficence when she was angry (“Maybe that’s where you get it from”), nor was there any resemblance to the much fairer Cynthia. Even in photographs it was there, the trope of the good girl and her wicked twin that had mysteriously followed them into adulthood, I thought, though Aunt Gina was older. Still, she was my forebear; I owed it to both my father and myself to find the truth. Why had she given him up?

My father had his own questions. With Nannie gone, his long-deferred desire compelled him to drive to Florida, where Aunt Gina, now 98, lived in a nursing home.

“I walked inside, and she was sitting in a wheelchair,” came his lively report. “I says to her, ‘I drove a thousand miles, and I’m gonna ask you one question. I want a straight answer.’” He pointed an index finger to demonstrate how he had done it. “I said it just like I’m saying it to you.”

“It’s true, he did,” my mother nodded.

“I says, ‘Are you my mother?’ and she said ‘yes.’”

He sat back proudly, as if he had figured out a puzzle that had long stumped him, except that this was not new data. It was satisfaction he was feeling, I realized, at having confronted this wire-thin, hard-as-nails woman who had loomed so large in his interior life. A mother who had done the unthinkable and relinquished her newborn.

Had he asked about his father? I wanted to know.

Aunt Gina had confessed that Ernie Ellis was indeed his father. But my father learned little more than that. She had begun to cry and he felt obligated to hold her, though he called them crocodile tears.

“I don’t trust her,” he concluded.

I wondered if he had felt longing, perhaps, or empathy. But I didn’t ask.

He had posed the question in the nick of time. Shortly afterwards, she died.

With both women gone, questions could now be asked openly. When my father applied for his Nova Scotia birth certificate, he received a “replacement” that named the place and date of his birth, but not his parents. I was outraged that his lineage could so casually be erased, as if he had dropped to earth from a spaceship. I turned to a website of digitized historical archives and a story soon emerged, but without coherence, like those first pieces of a puzzle that accidentally align.

A 1928 marriage certificate for Regina Goodwin and her first husband, Merwyn, said that she was 21, which would have meant she was born in 1907. But Regina’s Florida death certificate recorded her birth year as 1909, and the wedding license for her second marriage recorded it as 1911. These discrepancies suggested that she had lied on her first marriage license by adding four years to her age. A search for her birth certificate, which would ostensibly give the correct date, yielded nothing. Nova Scotia in the early 20th century, I reasoned, was sparsely populated with babies regularly born without doctors. The bonanza came unexpectedly with Nannie’s 1932 wedding license, which bore the names Cynthia Goodwin, Douglas R. Smith, Regina Goodwin, and Ernest Ellis.

My father’s birth parents had been present at the wedding of his adoptive parents, five years before his birth.

It seemed they had all been small-town friends.

I pushed on, finding a record of Ernest Ellis’s birth in 1910. But here was another surprise: In 1938, one year after Aunt Gina had given birth to my father, Ernest married a woman named Marie. The accumulating data swirled like a blizzard inside a snow globe; when they settled, the picture came into clearer focus. Born in 1944, Chuck was six years younger than my father. This meant that Aunt Regina and Ernest Ellis had carried on their affair well after Ernest had wed and—I would later learn—after he had started a family with his wife.

In other words, Aunt Gina hadn’t married him because he was already married.

Now I wondered about Ernest. Aunt Gina might have indeed been wild—she had, after all, likely lied about her age and borne two children with a married man—but what was his story? Death records showed that his mother had died within months of his birth; his father died twenty-five years later when his wagon got stuck on railroad tracks and was hit by a train. Ernest was recorded in the Nova Scotia census as living with his grandfather as a boy. Little else was revealed. I had hit a dead end.

I felt some emergent empathy for the man. Perhaps his mother’s death had left him starved for love. Perhaps he grew up ashamed, a motherless kid living under a grandfather’s roof. Perhaps his father had never recovered from his grief; there was no record of a second marriage or other children. There was likely more to the story, but who knew?

A timely 2019 phone call moved it along. I had written to the Nova Scotia office of child welfare, asking that my father’s adoption file be unsealed. But I received a letter demanding proof that his birth mother was deceased, a truly illogical requirement. The whole point was to identify an unknown parent, and I said as much when I wrote back. But I did have Aunt Gina’s death certificate, though about Ernest, I could say only that he had been born more than 100 years earlier and was thus likely dead. After several months with no reply, I made a long-distance call. An overworked staffer said that my father’s name was one of 200 on a waiting list.

“Lots of illegitimate children were given up back then,” she said ruefully.

Now in his eighties, my father had congestive heart failure and couldn’t wait indefinitely. I asked her tearfully to please—please—bump his name to the top of the list. Then I emailed her a photograph of my father in knickers and knee-socks, hoping his boyish face would tug at her heart.

A couple of weeks later, my father called.

“A big envelope came from Nova Scotia today.”

He hadn’t opened it. He was waiting for me.

Early the next day, we spread out the envelope’s contents, copies of 75-year-old social-worker notes. My father’s biological father was never named. “The family wishes to keep it a secret,” said the report. That was disappointing, but we already knew it. The real gift of the file was what it said about Douglas Ripley Smith. I read out loud:

Mr. Smith seems very much attached to Garth. He is a short man with a rugged complexion, very healthy in appearance, and a very hard worker. The child seemed very much devoted to him and followed him around a great deal.

“I did follow him around.” My father leaned in close, his blue eyes watery. “Remember that telescope in Nan’s kitchen? She would look for my father’s boat coming in and I would run to meet him. And—”

I sobbed instantly, and so did my father. I reached for his arm.

“He used to sit me between his legs in the Whippet,” he continued, struggling to smile. His dreamy eyes told me that he was right there, in the front seat with his father. “He would work the foot pedals, and I would get to turn the wheel—that big wooden wheel.”

“Why are you crying?” my mother asked as she passed by. “That’s not a sad memory, running to your father.”

Running to his father wasn’t. But the loss of the only man he had ever loved, was.

“It still bothers me,” he said finally, “that I never got to say goodbye.”

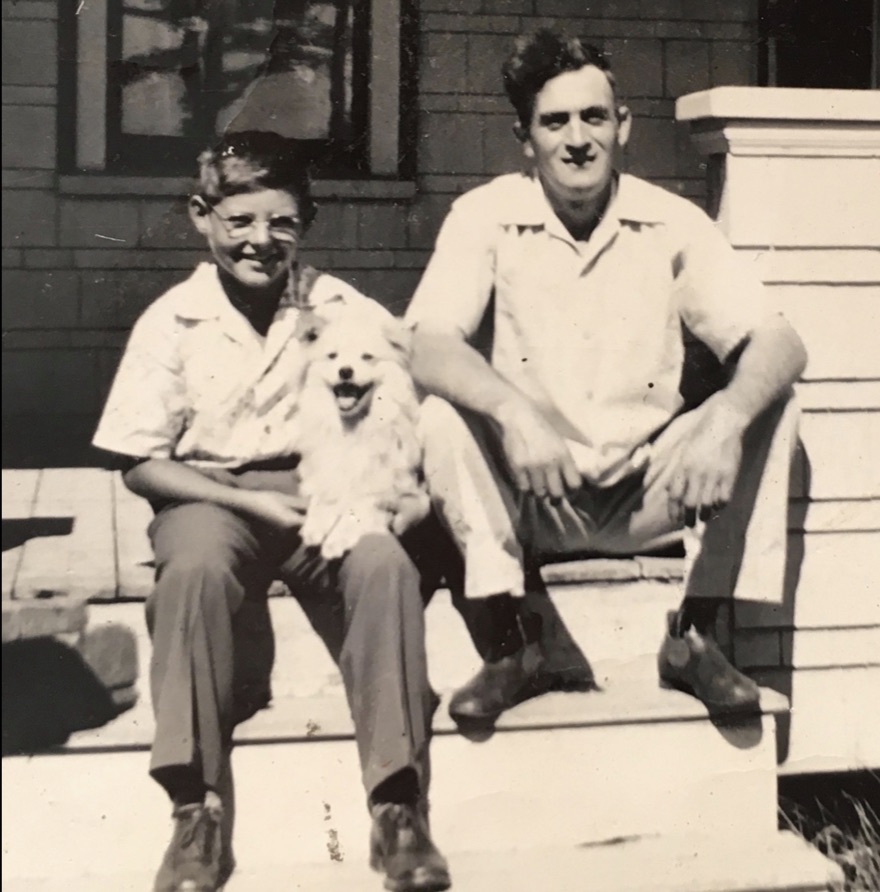

The story did not end there. My father was now in his early eighties, and I had an album of family photographs, many as yet unidentified. We spent hours examining them with a magnifying glass. I got the names of aunts and uncles and cousins, but more important, I got the stories of a boyhood long interred—rich, wonderful stories that revealed a depth of love and feeling I had not thought possible. There was the backyard at his grandmother’s cottage with an overturned dory and a clothesline of flapping sheets, behind it the trees he used to climb. There were accounts of Douglas’s musical talent on the rhythm bones and his spirited clogging. There was my father straddling the roof rafters of a half-built store where Douglas would eventually sell apples and ice cream and soap suds. There was the unheated Whippet, so cold on winter drives that my great-grandmother heated beach stones and wrapped them in wool to keep the passengers’ feet warm. There was the old barn my father burned down when the fire he started as a kid couldn’t be squelched by the village bucket brigade, and the pond his father had dug so he could raise chickens and ducks. There was my father sitting on a lobster trap with the two white rabbits and later, with a half-chow named Snookie, all, gifts from his father.

Some stories came unbidden, like his recollection of his first new bicycle.

“We got in the truck and he took me into town,” he said, laughing softly, “and we went into Spinney’s supply. It was a big store and up on the walls, up high”—he gazed up as if he were actually there—“were all these bicycles, hanging up. He told me, ‘I think it’s time you had a new bike.’ The one I liked was forest green, and that’s the one I picked.”

I couldn’t help but remember my father taking me to pick out a two-wheeler, an errand that must have reminded him of his father, though he never said so. I thought of the pen he built for our pet rabbits and the dog we had, as children. How many times had he walked in Doug’s footsteps, doing what his father had done, and I had never known? And how many times had I “followed my father a great deal,” as he had his?

Among the photographs of my father’s childhood was one I particularly liked because, at the age of sixteen, he could have been my twin. He stood next to Doug, almost having reached his father in height, and the two looked toward the camera and smiled. “That was the same year he died,” my father said, studying the snapshot with a magnifying glass. He leaned in and looked at Doug’s hand. “You can see where his thumb got ripped off.”

Huh? I said. I had studied that picture often and didn’t know what he was referring to. But there it was: The thumb on Doug’s right hand ended just before the knuckle—you could tell by comparing to the other hand. What had happened? I wanted to know.

“He was out on the boat, and he was hauling up the anchor, you know, on a rope,” my father said of an accident that happened when he himself was about nine years old, in 1947 or 1948. He hadn’t been there to witness when his father’s boat drifted and the rope let out, in the process wrapping itself around the man’s thumb. Someone must have grabbed and held onto him while they seized that fleeing rope, but the price of not getting dragged overboard was having most of his thumb pulled off. “You should have seen it,” my father said. “He had all these cords and veins hanging from his hand—it was ripped up good.” He likely meant tendons; there was probably also bone and shredded muscle. Doug would have been bleeding and in excruciating pain while the boat chugged back to Sandford, and while someone tied it up. He would have continued to bleed as he piled into a pickup truck that someone else drove the six or seven miles to the hospital. And in 1947 or 1948, there would have been rudimentary cleaning and stitching of the wound, nothing to re-attach, no reconstructive surgery. Doug—the fisherman and player of bones—would have lost the thumb that was just as essential to hauling lobster traps as it was to rattling the rhythm bones. Yet here was a photograph of thumb-less man standing next to his son and smiling as if he were the luckiest man in the world.

My grandfather, Douglas Ripley Smith, whom I never knew.

Prompted by that story, I was compelled to study another photograph that was pasted in the album: an unassuming man in wellies and a cap, his lunchbox tucked under his arm, his chest swelling as he pulled himself up for the picture, squinting a little in the bright sun that cast my grandmother’s long shadow on the ground in front of him. There was no artifice in the man’s visage, no posing for the camera, just the momentary cheer of a no-nonsense fisherman on his way to work. It was a stance I well recognized, having seen it many times when my own father left for work, a pickup truck similarly awaiting him.

This particular photograph elicited the saddest story of all. Long a sufferer of tuberculosis in a time before antibiotics, Doug had become sick with pneumonia the year my father turned seventeen. When Doug became so grievously ill that he had to be taken to the hospital, my father begged Nannie to be allowed to go, but she made him stay behind with his younger sister. He watched his sickly feverish father pile into the car that took him away forever. Doug died the next morning.

“It was the worst thing that ever happened to me,” my father said, avoiding my eyes. “The day he died was the day I lost my best friend. I cried non-stop for three days.”

This particular photograph elicited the saddest story of all. Long a sufferer of tuberculosis in a time before antibiotics, Douglas had become sick with pneumonia the year my father turned seventeen. When Douglas became so grievously ill that he had to be taken to the hospital, my father begged Nannie to be allowed to go, but she made him stay behind with his younger sister. He watched his sickly feverish father pile into the car that took him away forever. Douglas died the next morning.

“It was the worst thing that ever happened to me,” my father said, avoiding my eyes. “The day he died was the day I lost my best friend. I cried non-stop for three days.”

Imagining him as a boy crying for three days was almost more than I could bear, but I did. I sat with that sorrow, and I sat as well with the knowledge that he had quit school to help support Nannie. When she remarried six months later, he left Sandford for good. He landed in Massachusetts where, within a few years he would meet and marry my mother, eventually growing a family of four daughters whom he supported with demanding work in construction. His life was, like his father’s, one of the ordinary integrity of consistently showing up rather than the spectacular irresponsibility of Ernest Ellis. But my father didn’t seem to know just how extraordinary he was. Contemplating the taciturn gloom that had seemed to suffuse our household, I began to perceive how his life had been shaped by traumatic loss of the father whose shining face bore no trace of the shame that infused the false “family secret” narrative. My father’s stories always came back to a man who had loved him, it seemed, with something close to reverence.

Douglas Ripley Smith, a life too soon cut short, was the embodiment of uncelebrated good.

“Although being in poor health for some time,” his obituary said, “being one not given up easily under the strain of sickness, he bore much to himself. A staunch friend to all who knew him of a genial and pleasant personality, there is no way we can turn but what he will be missed on every hand. We here in Sandford have lost a prominent citizen, and our hearts are filled with deepest sorrow.”

The enormity of this loss was amplified by the last and most horrifying discovery I would make, entirely by accident. Digging aimlessly through historical records, I came across the death certificate for a three-month old boy who had died of malnutrition. He had been born three years before my father, and Aunt Gina and Ernest Ellis had been his parents.

I recoiled from the record as if stung. I had visited the family cemetery in Nova Scotia and had likely walked near his overgrown unmarked grave. My great grandmother had been a midwife and had mothered many babies. Had Aunt Gina cruelly neglected her infant, or had he succumbed to a disease of infancy? I would never know, but the cold hard fact of death underscored the fate for many unwanted children. My father’s older brother had entered then left this world unacknowledged and perhaps even un-mourned, and the persons who gave him life had gone on to have two more unwanted babies who they had—mercifully—given up.

The shock and grief lingered. For two decades I had focused on finding my father’s biological father, Ernest Ellis, whose presence was enlarged not by what he had done, but by what he had not done. He had not married Aunt Gina. He had not stopped sleeping with her after he married another woman. He had made and abandoned babies with a wanton carelessness that seemed unforgivable.

The beating heart of the story was Douglas Ripley Smith, who had, without fanfare, taken in my father, kept him clothed and fed, and left him with a storehouse of such deeply loving and warm memories that my father had buried rather than revisit them. To remember them elicited an anguish I could barely comprehend.

“Quit making Dad cry,” one of my sisters said when she learned what I had found out. It was a misapprehension of perhaps the gravest kind. I was not foisting grief on my father, but rather, bearing witness to sorrow that he had too long carried alone. In bearing witness, I had in a small way restored some of the joy of a simple but rich and happy boyhood.

I had also gained something my sister might not perceive, and that was greater self-understanding. In situating my own life on a larger landscape, I shed the shame I once assumed had originated in me. Our father was a man of tremendous resilience who had endured the hardship of his own father’s death, the unspoken knowledge that his birth mother hadn’t wanted him, and the rigors of succeeding in a new country. A man who leaned into hard work, he was not given to complaints or self-pity. But he had also locked away the very grief that, expressed, opened a door to love.

One day he said, “I have a picture I want to show you.” From the deepest slot in his wallet he pulled a ragged snapshot, yellowed by tape and cut to size, of a plump-legged baby. I recognized my younger self instantly.

“I’ve carried that in my wallet practically since you were born,” he said.

Unbeknownst to me, the longed-for softness had always been within reach.

Children cannot comprehend the enormity of the ocean, but adults—and fisherman in particular—can. They know its grandeur and its dangers as well. The beauty of what Douglas Ripley Smith did is captured by the image of the Sandford breakwater, so artfully constructed that the children splashing in its confines are blissfully unaware of the tides that could swallow them. Without fanfare, the breakwater preserves their innocent and happy play; soon enough, they will grow into an adulthood unprotected from harsher elements. For a time, my father’s father gave him that happy innocence, and what a gift it was.

A grand gift, a gift of grace.